‘Good Night, and Good Luck’ review: George Clooney makes his Broadway debut in a sleepy newsroom play

Theater review

GOOD NIGHT, AND GOOD LUCK

One hour and 45 minutes with no intermission. At the Winter Garden Theatre, 1634 Broadway.

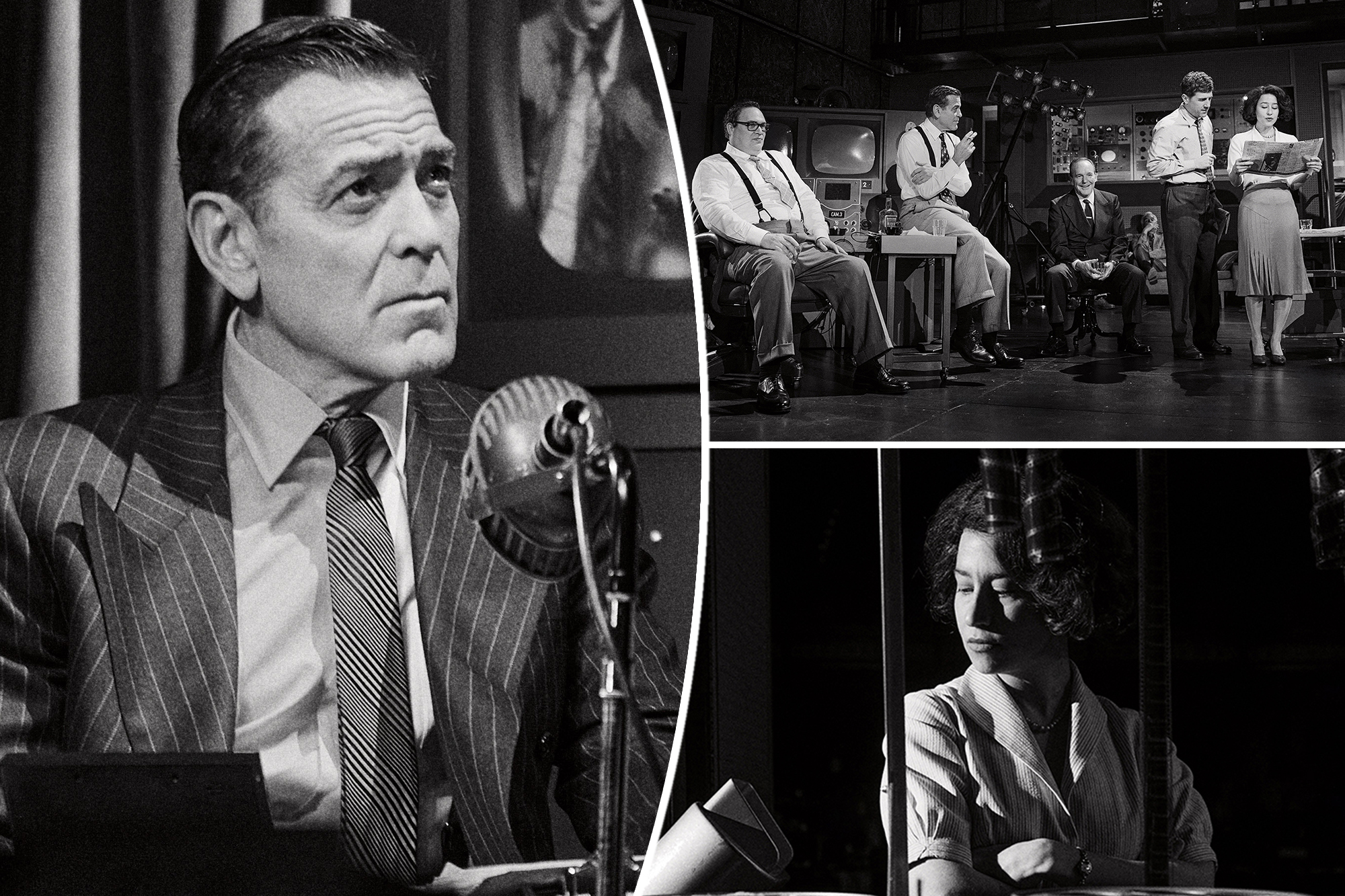

“Good Night, and Good Luck,” the play that opened Thursday at the Winter Garden Theatre, is a big story with a huge set and an enormous star.

So it comes as a surprise that the impression left by the dusty historical drama as the audience pours out onto Broadway is so small and fleeting. Good Night, and What’s For Dinner?

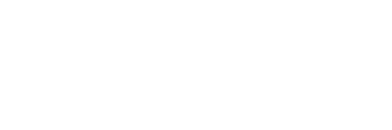

The celeb du jour is George Clooney, who makes his Broadway debut — twice. He’s both the co-playwright and stars in the genteel role of Edward R. Murrow, the CBS newsman who waged a public battle with Communist-hunting Sen. Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s.

“Good night, and good luck,” was the man’s famous sign-off.

That line is spoken many times in this attractive but empty show. I enjoyed looking at the massive and elaborate TV studio and retro suits for a while. But you can’t light a damp log.

This schlep is a project Clooney is clearly very passionate about.

Way back in 2005, he directed and wrote the movie the Broadway show is based on, netting Oscar nominations for Best Picture and Best Director, among others.

In that film, David Strathairn played Murrow. Twenty years later, Clooney is finally the right age to try his hand at the “See It Now” host onstage, even if it’s laughable that one character says to him, “You have a face for radio.” Yeah, and I have a résumé for astrophysics.

The “Oceans 11” actor’s time-capsule performance is assured, confident and occasionally aided by cameras and TV screens — tools he understands much better than proscenium arches. The audience watches his blown-up broadcasts as he delivers stone-faced monologues straight to the lens.

He succeeds about as well as the beige script allows him to. Which is to say, as well as he allows himself to.

Clooney the writer has not been so generous to Clooney the actor. The part is milquetoast, like a sanded-down version of Atticus Finch who speaks with the repetitive calm of a hypnotist.

He’s even-keeled and professional to a fault, as if gunning for sainthood. That might have been the honest case with Murrow, but figureheads are less fascinating than fleshed-out people. They need to find their humanity. Otherwise, we start finding the articles in the Playbill.

And as Murrow’s fight becomes existential, with powerful network execs like William S. Paley (a terrific Paul Gross) growing worried as the man controversially reshapes what TV news is, the play doesn’t build to a crescendo or captivate along the way.

There are other missteps in the production directed by David Cromer.

A talented jazz band in the corner turns a rebellious newsroom shaken by fear into a relaxing martini lounge.

And the buzzing hive of journalists and backstage crew characters played by the cast of more than 20 actors, all of whom do good work as they shout in New York accents, are treated as little more than set dressing.

The closest we come to getting to know anybody is Shirley Wershba (Ilana Glazer) and Joe Wershba (Carter Hudson), producers who conceal the fact that they’re married at work. The point of them? I couldn’t tell you.

Most crucially, it was a mistake not casting a, well, living actor to play McCarthy and instead to rely on archival footage of the senator’s accusatory hearings and his rebuttal to Murrow’s stinging critique.

We always feel like we’re watching grainy old clips shot 70 years ago and not experiencing a dangerous event unfold before our eyes.

A traumatic and consequential chapter in American history becomes nostalgic, and few things are deadlier onstage than nostalgia.

Well, I can think of one that is: video montages.

During the last few minutes, the play switches into strident lecture mode and projects a flurry of clips showing how TV news has evolved from old-school grandfatherly newsmen whose politics were kept close to the vest to the opinionated and fiery hosts of today.

It’s unnecessary and obvious; shoveling textureless meaning into the troth.

By the end, “Good Night, and Good Luck” manages what evening news shows have reliably done for decades: It makes the viewer sleepy.